THE MYSTERY OF MUCUS!

By Rebecca Campbell Gibbel, MS, DVM

- WHAT GOOD IS SLIME?

For many marine animals, mucus is an essential part of their lives, providing a protective barrier. Clownfish have a mucous coating on the surface of their skin, gills and gut that is three to four times thicker than other similarly sized fish. This slippery surface reduces friction while swimming, limits dehydration, and prevents bacterial accumulation. Mucus is produced constantly by special goblet cells in the epidermis, and it is an essential part of the piscine innate immune system [5]. Cnidarian animals, like corals and anemones, that live stationary lives are threatened by burial in sediment, and they have surface mucus that continually sloughs off, removing adherent sand and bacteria. Mucus has such an important role for them that their production of it may account for as much as 40% of their daily fixed carbon supply [21]. Mucus is a major component of the innate immune system for cnidarians as well as fish, providing both physical protection against invading microorganisms and producing antimicrobial compounds. To prevent anemones’ tentacles from adhering to each other, their mucus has carbohydrate anti-adhesives [2], and it also contains defensive toxins [14]. But wait, there’s more – clownfish and anemones even have chemical communication mediated by their mucus!

Figure 1. A pair of clownfish confronting a photographer. Photo by Caroline Rogers.

- AN ICONIC SYMBIOSIS: What’s in it for me?

Long before Nemo rocketed to fishy fame, the interdependent relationship between clownfish and anemones has provided a classic example of symbiosis, with both parties benefitting from the unusual partnership. It is estimated that this relationship has been in existence for at least 10 million years — so they’ve had plenty of time to work things out [6].

Although the striking orange and black species are typically considered to be the classic clownfishes, the terms “anemonefish” and “clownfish” are actually interchangeable. For the fish, a relationship with an anemone is obligate, meaning they don’t survive long in the wild without the protection of an anemone host. For the participating anemones, the partnership is highly beneficial, yet oddly only ten of the 1170 species of sea anemones in the Pacific and Indian oceans form associations with anemonefish [17].

Anemones are in the fierce phylum of cnidarians, along with corals and jellyfish. All these animals have harpoon-like stinging cells called nematocysts, which repel predators and are used to stun and capture prey, which ranges from tiny zooplankton to small fish. There is a wide spectrum of toxicity of anemones, and the moderately and highly toxic species are easily able to kill and consume reef fish. Clownfishes’ ability to live without injury amidst the stinging tentacles of anemones has piqued the interest of scientists for centuries. The many benefits of the relationship are in the table below.

Table 1. Advantages of a symbiotic partnership for anemonefish and for anemones

| ADVANTAGES FOR ANEMONEFISH | ADVANTAGES FOR ANEMONE HOST |

| Living in a host that stings and kills predatory reef fish increases survival | Anemonefish aggressively drive away anemone predators which improves anemone survival [19] |

| Clownfish eggs are laid within anemones and are protected by their stinging tentacles [19] | The anemonefish deposits waste in the anemone which is recycled into nutrients for the anemone |

| Anemonefish that are hosted by anemones have very long lifespan- up to 35 years, vs. maximum of 5 to 10 for similarly sized fish [14] | Movement of the fish prevents water stagnation, reduces sedimentation and aerates the anemone tentacles |

| Clownfish can scavenge food that the anemone has captured, allowing them to stay on duty with the host | Fish remove and eat parasites off the anemone |

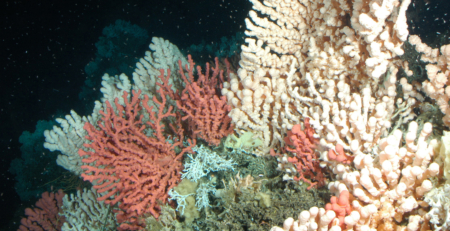

Figure 2. One of only ten anemones that host clownfish, though color morphs are abundant. Photo by Caroline Rogers.

- SELECTION AND CONNECTION

TINDER FOR FISH?

Since it is such a major benefit for an anemonefish to claim an anemone, how is it determined which fish wins that lottery? Some clownfish species like Amphiprion frenatus and A. sebae are extreme specialists that only pair up with a single anemone species. Others are less selective, like the A. ocellaris clownfish that pairs with up to three types of anemones, while low maintenance generalists like A. clarkii can live with up to 10 anemone species [15]. Body size is a major factor in the competition for prime real estate. Large specialist anemonefish tend to completely monopolize their host to the point where a spacious anemone is only occupied by one breeding pair of large fish. Smaller anemonefish species get pushed to less desirable anemones or forced into holding patterns near an anemone [9]. Some clownfish, like A. biaculeatus, have developed large intimidating cheek spines giving them a favorable competitive advantage, since their main value to the anemone is their ability to ward off predatory fish. A final way that anemonefish improve their odds of a swipe to the right is by behaving in a perpetually aggressive manner. They may confront, bite and chase any fish or diver who gets too close, and they will harass their conspecifics that are beneath them on the waiting list [4].

Figure 3. Guard dogs and clownfish are most effective at driving away intruders if they are big, scary and mean

HOW DO FISH FIND THEIR ANEMONES?

Even before entering the competition to occupy a prized anemone, clownfish must first locate a potential slimy host which might be a long distance away. After hatching from eggs which were laid beneath the arms of their anemone, the clownfish fry emerge and have a brief pelagic (open water) period. But the juvenile anemonefish must find protective anemones quickly. Experiments have found that they can recognize their natal anemone host species by following waterborne chemical cues – essentially smelling the mucus secreted by the anemone species under which they were born [7].

TOXIC RELATIONSHIPS

There is a considerable variety of toxicity among the ten species of sea anemones that form symbiotic relationships with clownfish. The anemone toxins attack the neurologic and hematologic systems of the anemone’s prey and cause the same damage to unacclimated clownfish. A study by Nedoskyko et al. (2014) demonstrated that the most preferred anemones are those with intermediate venom toxicity. The most toxic anemones had few clownfish associates, presumably because of the additional difficulty for the fish to avoid being envenomated themselves. The anemonefish that manages to take advantage of the most toxic anemone is armored with an extremely thick mucus coat. Anemonefish also must select oviposition sites (which is a fancy term for a nest) by balancing the need to have an anemone that will protect the developing embryos but that will not harm the hatching larval fish.

Figure 4. Toxicity of anemone venom compared to number of anemonefish species that associate with them, from Nedoskyko et al., 2014.

- MUCUS COMPATIBILITY: The key to a happy life?

ACCLIMATION BEHAVIOR

Before any symbiotic association is established, an anemonefish must first become acclimated to a host anemone, or else the fish will be stung and perhaps killed. This high stakes alliance is initiated by the fish with stereotypical behavior patterns. First the fish makes cautious contact by gingerly nibbling and nosing the anemone tentacles. Then the fish touches the anemone with its pectoral fins and finally rubs its entire body along the anemone tentacles [1]. Without a period of acclimation, the clownfish are stung by the anemones, but once fully acclimated, the fish can move freely among the tentacles without the anemone stinging the fish [11]. The synthesis of the anemone’s toxins has a metabolic cost, and it’s advantageous not to waste ammunition on a partner fish.

MICROBIOME MERGING

Part of the mutual acceptance process between fish and anemone begins before the first physical contact. In experiments housing anemones and clownfish in the same tank, with no physical contact, a convergence occurs between the distinct bacterial communities that live on the surfaces of both the anemonefish and the anemones. This modification of microbial signatures has been proposed to play an essential role in establishing the partnership [18].

MUCUS MATCHING

And now we have arrived at the biggest question: how do anemonefish avoid being stung by their host anemone? Scientists have known for decades that the key to this puzzle has to do with mucus– that of the clownfish and also that of the anemone. Is the fish disguising itself to taste like an anemone by anointing itself with the host’s mucus? Is this what discourages a host anemone from stinging an acclimated clownfish? Are the anemonefish actually being stung but are just immune to the sting? Years of study have assembled the components that help answer these questions. Here are key pieces of this puzzle:

- Some anemonefish have innate protection against stings from certain anemone species, but not from others. However, most clownfish must work to acquire and maintain this protection [8]. Since there are so many pairings between different species of anemonefish and anemones, it is not surprising that differing strategies have evolved.

- Anemonefish can develop resistance to a host anemone by simply being exposed to the anemone’s mucus in a tank of water [12].

- If a symbiotic anemonefish’s skin mucus is carefully removed after the acclimation process, the anemone no longer recognizes the fish as a friend and will attack it [22]. And if the anemonefish is merely separated from its anemone for two months, it becomes de-acclimated and becomes vulnerable to being stung again [6].

- The anemonefish collect surface proteins from the host and incorporate these antigens into their mucus, which then serves as a chemical camouflage that makes the fish resemble the host. These proteins are not present in fish mucus that do not inhabit a host anemone [7].

- When a host anemone is presented with the mucus from an acclimated clownfish the anemone has significantly reduced nematocyst firing, and anemones have a lesser inclination to sting fish species that usually associate with them, even if not acclimated [10].

With these clues taken together, the answer seems to be that acclimation for a harmonious partnership is a bi-directional process. The anemones learn not to fire off their toxins, and the anemonefish learn to outfit themselves in mucoid uniforms to identify themselves as members of the home team. Like any true partnership, both sides make accommodations for the good of the relationship!

Figure 5. A pair of Pink Anemonefish nestled in the tentacles of their host anemone. Photo by Rebecca Gibbel

REFERENCES:

- Balamurugan, J., Kumar, T. A., Kannan, R., & Pradeep, H. D. (2014). Acclimation behaviour and bio-chemical changes during anemonefish (Amphiprion sebae) and sea anemone (Stichodactyla haddoni) symbiosis. Symbiosis, 64, 127-138.

- Bavington, C.D.; Lever, R.; Mulloy, B.; Grundy, M.M.; Page, C.P.; Richardson, N.V.; McKenzie, J.D. Anti-adhesive glycoproteins in echinoderm mucus secretions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 139, 607–617

- Brooks, W. R., & Mariscal, R. N. (1984). The acclimation of anemone fishes to sea anemones: protection by changes in the fish’s mucous coat. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 80(3), 277-285.

- Buston, P. M. (2003). Mortality is associated with social rank in the clown anemonefish (Amphiprion percula). Marine Biology, 143, 811-815.

- Dash, S., Das, S. K., Samal, J., & Thatoi, H. N. (2018). Epidermal mucus, a major determinant in fish health: a review. Iranian journal of veterinary research, 19(2), 72.

- Da Silva, K. B., & Nedosyko, A. (2016). Sea anemones and anemonefish: a match made in Heaven. The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future: The world of Medusa and her sisters, 425-438.

- Elliott, J. K., Mariscal, R. N., & Roux, K. H. (1994). Do anemonefishes use molecular mimicry to avoid being stung by host anemones?Journal of experimental marine biology and ecology, 179(1), 99-113.

- Elliott, J. K., & Mariscal, R. N. (1997). Acclimation or innate protection of anemonefishes from sea anemones?. Copeia, 284-289.

- Fricke, H. W. (1979). Mating system, resource defence and sex change in the anemonefish Amphiprion akallopisos. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 50(3), 313-326.

- Hoepner, C. M., Fobert, E. K., Rudd, D., Petersen, O., Abbott, C. A., & Da Silva, K. B. (2024). Friend, food, or foe: sea anemones discharge fewer nematocysts at familiar anemonefish after delayed mucus adaptation. bioRxiv, 2024-02.

- Mariscal, R. N. (1972). Behavior of symbiotic fishes and sea anemones. In Behavior of Marine Animals: Current Perspectives in Research Volume 2: Vertebrates (pp. 327-360). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Mebs, D. (2009). Chemical biology of the mutualistic relationships of sea anemones with fish and crustaceans. Toxicon, 54(8), 1071-1074.

- Murata, M., Miyagawa-Kohshima, K., Nakanishi, K., & Naya, Y. (1986). Characterization of compounds that induce symbiosis between sea anemone and anemone fish. Science, 234(4776), 585-587.

- Nedosyko AM, Young JE, Edwards JW, Burke da Silva K (2014) Searching for a Toxic Key to Unlock the Mystery of Anemonefish and Anemone Symbiosis. PLoS ONE 9(5): e98449. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098449

- Nguyen, T. H. T. (2020). Adaptation of anemonefish to their host anemones: From genetics to physiology.

- Nguyen, H.-T. T., Zhao, M., Wang, T., Dang, B. T., Geffen, A. J., & Cummins, S. F. (2024). Sea anemone–anemonefish symbiosis: Behavior and mucous protein profiling. Journal of Fish Biology, 105(2), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15772

- Rodríguez, E., Fautin, D. G., & Daly, M. (2022). World list of Actiniaria. World Register of Marine Species.

- Roux, N., Lami, R., Salis, P., Magré, K., Romans, P., Masanet, P., Lecchini, D., & Laudet, V. (2019). Sea anemone and clownfish microbiota diversity and variation during the initial steps of symbiosis. Scientific reports, 9(1), 19491.

- Saenz-Agudelo, P., Jones, G. P., Thorrold, S. R., & Planes, S. (2011). Detrimental effects of host anemone bleaching on anemonefish populations. Coral Reefs, 30, 497-506.

- Schligler, J., Blandin, A., Beldade, R., & Mills, S. C. (2022). Aggression of an orange-fin anemonefish to a blacktip reef shark: a potential example of fish mobbing? Marine Biodiversity, 52(2), 17.

- Wild, C.; Woyt, H.; Markus Huettel, M. Influence of coral mucus on nutrient fluxes in carbonate sand. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 2005, 287, 87–98.

- Winn, H. E., & Olla, B. L. (2012). Behavior of marine animals: Current perspectives in research.